The Real Johnny Appleseed Brought Apples—and Booze—to the American Frontier

The apples John Chapman brought to the frontier were very different than today's apples—and they weren't meant to be eaten.

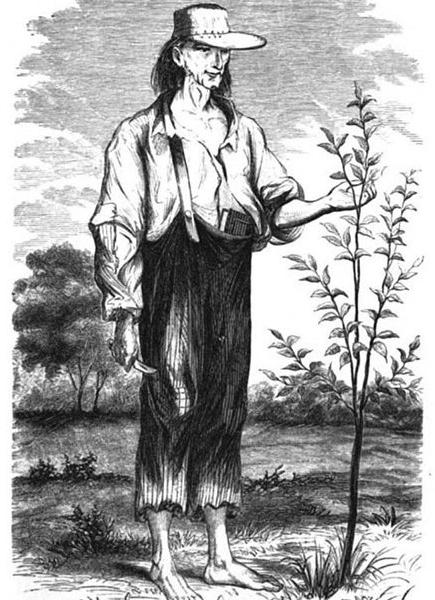

On n a family farm in Nova, Ohio, grows a very special apple tree; by some claims, the 175 year old tree is the last physical evidence of John Chapman, a prolific nurseryman who, throughout the early 1800s, planted acres upon acres of apple orchards along America's western frontier, which at the time was anything on the other side of Pennsylvania. Today, Chapman is known by another name—Johnny Appleseed—and his story has been imbued with the saccharine tint of a fairytale. If we think of Johnny Appleseed as a barefoot wanderer whose apples were uniform, crimson orbs, it's thanks in large part to the popularity a segment of the 1948 Disney feature, Melody Time, which depicts Johnny Appleseed in Cinderella fashion, surrounded by blue songbirds and a jolly guardian angel. But this contemporary notion is flawed, tainted by our modern perception of the apple as a sweet, edible fruit. The apples that Chapman brought to the frontier were completely distinct from the apples available at any modern grocery store or farmers' market, and they weren't primarily used for eating—they were used to make America's beverage-of-choice at the time, hard apple cider.

"Up until Prohibition, an apple grown in America was far less likely to be eaten than to wind up in a barrel of cider," writes Michael Pollan in The Botany of Desire. "In rural areas cider took the place of not only wine and beer but of coffee and tea, juice, and even water."

It was into this apple-laden world that John Chapman was born, on September 26, 1774, in Leominster, Massachusetts. Much of his early years have been lost to history, but in the early 1800s, Chapman reappears, this time on the western edge of Pennsylvania, near the country's rapidly expanding Western frontier. At the turn of the 19th century, speculators and private companies were buying up huge swathes of land in the Northwest Territory, waiting for settlers to arrive. Starting in 1792, the Ohio Company of Associates made a deal with potential settlers: anyone willing to form a permanent homestead on the wilderness beyond Ohio's first permanent settlement would be granted 100 acres of land. To prove their homesteads to be permanent, settlers were required to plant 50 apple trees and 20 peach trees in three years, since an average apple tree took roughly ten years to bear fruit.

Ever the savvy businessman, Chapman realized that if he could do the difficult work of planting these orchards, he could turn them around for profit to incoming frontiersmen. Wandering from Pennsylvania to Illinois, Chapman would advance just ahead of settlers, cultivating orchards that he would sell them when they arrived, and then head to more undeveloped land. Like the caricature that has survived to modern day, Chapman really did tote a bag full of apple seeds. As a member of the Swedenborgian Church, whose belief system explicitly forbade grafting (which they believed caused plants to suffer), Chapman planted all of his orchards from seed, meaning his apples were, for the most part, unfit for eating.

It wasn't that Chapman—or the frontier settlers—didn't have the knowledge necessary for grafting, but like New Englanders, they found that their effort was better spent planting apples for drinking, not for eating. Apple cider provided those on the frontier with a safe, stable source of drink, and in a time and place where water could be full of dangerous bacteria, cider could be imbibed without worry. Cider was a huge part of frontier life, which Howard Means, author of Johnny Appleseed: The Man, the Myth, the American Story, describes as being lived "through an alcoholic haze." Transplanted New Englanders on the frontier drank a reported 10.52 ounces of hard cider per day (for comparison, the average American today drinks 20 ounces of water a day). "Hard cider," Means writes, "was as much a part of the dining table as meat or bread."

John Chapman died in 1845, and many of his orchards and apple varieties didn't survive much longer. During Prohibition, apple trees that produced sour, bitter apples used for cider were often chopped down by FBI agents, effectively erasing cider, along with Chapman's true history, from American life. "Apple growers were forced to celebrate the fruit not for its intoxicating values, but for its nutritional benefits," Means writes, "its ability, taken once a day, to keep the doctor away..." In a way, this aphorism—so benign by modern standards—was nothing less than an attack on a typically American libation. Today, America's cider market is seeing a modest—but marked—resurgence as the fastest growing alcoholic beverage in America. Chapman, however, remains frozen in the realm of Disney, destined to wander in America's collective memory with a sack full of perfectly edible, gleaming apples.

But not all of the apples that came from Chapman's orchards were destined to be forgotten. Wandering the modern supermarket, we have Chapman to thank for varieties like the delicious, the golden delicious, and more. His penchant toward propagation by seed, Pollan argues, lent itself to creating the great—and perhaps more importantly—hardy American apple. Had Chapman and the settlers opted for grafting, the uniformity of the apple product would have lent to a staid and relatively boring harvest. "It was the seeds, and the cider, that give the apple the opportunity to discover by trial and error the precise combination of traits required to prosper in the New World," he writes. "From Chapman's vast planting of nameless cider apple seeds came some of the great American cultivars of the 19th century."

While the apple find its geographic origin in the area of modern-day Kazakhstan, it owes most of its popularity to the Romans, who became masters of apple grafting, a technique wherein a section of a steam—with buds—from a particular type of apple tree is inserted into the stock of another tree. Grafting is an integral part of cultivating apples, as well as grapes and fruit trees, because the seed of an apple is basically a botanic roulette wheel—the seed of a red delicious apple will produce an apple tree, but those apples won't be red delicious; at most, they'll only barely resemble a red delicious, a characteristic that classifies them as "extreme heterozygotes" of the biological world. Because of its intense genetic variability, fruit grown from apple seed, more often than not, turned out to be inedible. Apples grown from the seed are often called "spitters," from what you'd likely do after you took a bite of the fruit. According to Thoreau, an apple grown from seed tastes "sour enough to set a squirrel's teeth on edge and make a jay scream."

When apples made their way to colonial America, they came first in the form of graftings—budded stems from the settlers favorite European trees, which they hoped to bring with them to the New World. But the soil of America turned out to be less hospitable than the soil the colonialists had known in Europe, and their apple trees grew poorly. Moreover, as William Kerrigan writes in Johnny Appleseed and The American Orchard, early settlers lived in a world where land was abundant but labor was scarce; grafting was a delicate technique that required finesse and time, whereas growing apples from seeds produced a crop with relatively little effort. Eventually, settlers turned to growing apples from seed, producing "spitters" unfit for eating—but immensely well suited to fermenting into alcoholic quaffs.

Оставить комментарий

Для комментирования необходимо войти через

![]() Вконтакте

Вконтакте