Life on The Gate: Working on the Golden Gate Bridge 1933-37

When it opened in 1937, the Golden Gate Bridge was the longest suspension bridge ever built, constructed in one of the world’s most challenging settings. For the men who poured the concrete, and drove in each steel rivet, it was a life changing experience.

It was on November 18, 1936, that the two sections of the main span were joined in the middle.

In many ways, Fred Brusati was typical of the kinds of men who worked building the Bridge. His parents had emigrated from Milano, Italy to Montana, where Fred’s father worked as a copper miner. After Fred was born in 1911, his parents moved to San Rafael.

Fred spent a year in high school, then went looking for work.

Fred Brusati.

“One day I heard they were going to start the Golden Gate Bridge,” he told interviewer Harvey Schwartz in 1987, as part of an oral history project conducted by Labor Archives and Research Center at San Francisco State University.

“And I says well, I’ll try it. I never been up 746 feet but I’ll try it anyhow.”

Tough work, in tough times

It was the middle of the Great Depression. Mary Currie, a spokeswoman for the Golden Gate Bridge District, says getting a job on the Golden Gate Bridge was like winning the lottery.

“The men would line up and wait for a chance to get a job, literally hoping someone would hurt themselves so they’d be the one to get the job.”

Slim Lambert, a cowboy from Washington state, was hired as a roustabout. He helped build a temporary railway to carry equipment across the bridge span, making about 10 dollars a day.

“Things were a lot different in those days,” he told Schwartz.

“You hardly ever slowed down to a trot. If you went to the restroom and stayed more than 30 seconds, the boss would come see what was wrong with you. Lots of men were fired right on the spot, if the boss thought they were malingering a little bit. There was men waiting right there for a job.”

Construction challenges

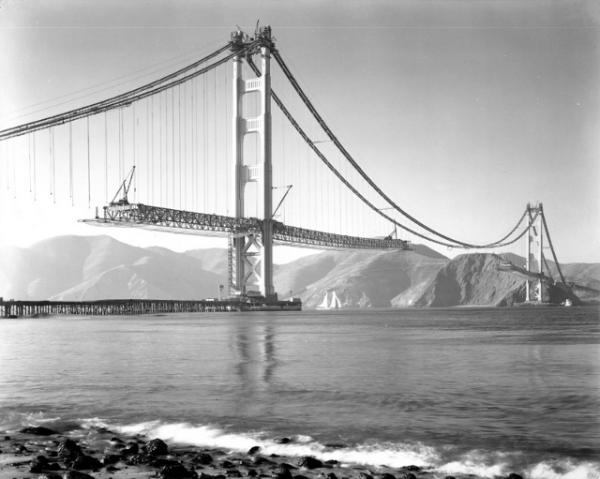

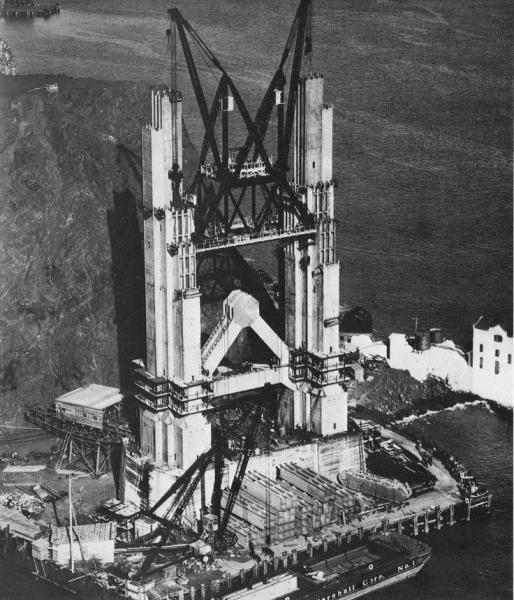

The Marin tower of the Golden Gate Bridge under construction in 1933.

Construction of the Golden Gate Bridge marked the first time anyone had built a suspension bridge support with a tower in the open ocean. The conditions, above and below the water, were harsh.

Divers faced powerful currents as they helped anchor the massive concrete bridge support onto the ocean floor.

And up on the towers, workers stuffed newspapers in their jackets to keep warm.

Martin Adams, born in Arkansas in 1912, called the bridge “the coldest place I’ve ever worked.”

“You put all the clothes on you had and worked, worked hard, or you’d freeze.”

Cold was the least of their concerns. Bridge spokeswoman Mary Currie says workers on the bridge didn’t just fear death. They expected it.

“At the time, the industry standard was that for every million dollars spent, there would be a loss of life,” says Currie.

The bridge was estimated to cost $35 million. But structural engineer Joseph Strauss, who headed the project, was determined to keep workers safe. Hard hats were required. And Strauss insisted on one feature that Mary Currie says was at the time completely novel: A safety net.

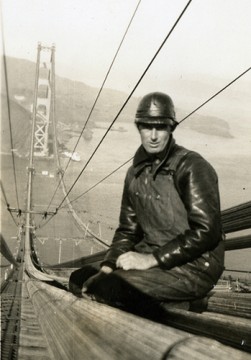

Workers on the main cable of the Golden Gate Bridge.

“It was a $130,000 expense at the time, which was considered an exorbitant expense. But he really fought for it and was able to get the board of directors to permit it.”

Over four years of construction, the safety net saved the lives of 19 men. They called themselves the “Halfway to Hell Club.”

For nearly four years, the Golden Gate Bridge project seemed charmed with an almost perfect safety record. And then, one day, everything changed.

For the roadway construction, Strauss insisted on the addition of the $130,000 safety net.

The collapse

The task that day, on February 17th, 1937 was to remove a wooden scaffold that had been built underneath the bridge platform. To reach it, workers had hung a temporary catwalk. Each time they stripped off a section of wood, workers would move the catwalk another few feet.

“And as they started to move it,” recalled Martin Adams, who was standing nearby, “that’s when it went down. 9:20 in the morning, it went down.”

The catwalk hadn’t been attached properly. It broke off and plunged into the ocean, dragging the safety net with it.

Fred Brusati was working nearby when he heard someone shout that the catwalk had fallen. He rushed over to the side and saw a man clinging to a piece of steel. Brusati and a few others threw the man a rope, and hauled him up to safety.

“The man had a pipe in his mouth,” recalled Brusati. “He didn’t drop the pipe or nothing. He just started to walk toward San Francisco and I never did see him back there again.”

Dummatzen’s family after their son’s death.

The real tragedy was below. Twelve men had fallen 220 feet into the water. One of them was Slim Lambert.

“People ask me what went through your mind? The only thing that went through my mind was survival. I knew that to have a prayer, I had to hit the water feet first.”

But when Lambert hit the water, his legs tangled in the safety net.

“That’s the only time I panicked during that whole thing,” said Lambert. “I was caught in the net and the net was headed for the bottom.”

Fred Dummatzen.

Lambert plunged so deep that when he surfaced he was bleeding from his ears. Bridge debris was everywhere.

“I got a couple of planks together for my self first, and then I saw Fred thrashing about. So I got him.”

Fred Dummatzen was 24 years old. Lambert pulled him up onto the planks and waited.

“I heard this power boat coming in. Put put put.”

It was a crab fisherman, coming in from sea. Lambert says there was so much junk in the water, he worried the driver would pass right by.

“He took another look around and his eye hit me. What I relief. I figured, by gosh, we’re gonna make it.”

Dummatzen died on the crab boat. But Lambert and another man, 51-year old carpenter named Oscar Osberg, survived the fall. Today, there’s a plaque on the south western side of the bridge at the entrance to the west sidewalk dedicated to the ten men who died that day.

Mary Currie says the workers she’s talked to don’t really remember the cold, or the danger. They felt lucky to be there.

At a time when the rest of the country was struggling to get by, six Bay Area counties agreed to spend what seemed like a fortune on a suspension bridge longer than any the world had ever seen.

“It was the people who had to rise up and see this as a symbol of hope, imagination, stick-to-itiveness,” says Currie. “They saw this bridge as something that would change their lives.”

And that, she says, was a pretty gutsy thing to have done.

Оставить комментарий

Для комментирования необходимо войти через

![]() Вконтакте

Вконтакте