IDAHO TEACHER TRIES TO MOVE FORWARD AFTER SEX ED COMPLAINT

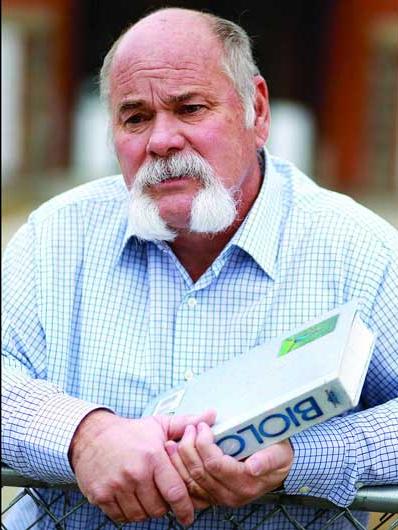

DIETRICH — Tim McDaniel’s world turned upside down in 2013.

The Dietrich science teacher found out four parents filed an ethics complaint against him as a result of a sex education lesson he taught.

The Idaho Professional Standards Commission dropped the complaint and didn’t take action. But news of the complaint in Dietrich — a Lincoln County town with 330 residents — made national headlines. McDaniel’s backers created a Facebook page, “Save The Science Teacher,” which received about 700 likes.

Nearly three years later, McDaniel is still teaching biology in Dietrich. But after the ethics complaint, things will never be the same.

“It made me fall apart,” he said in early March. “Honestly, it’s something I’ve never forgot.”

McDaniel stopped going to church and school basketball games. He said he’s uncomfortable around other people — something that was never a problem before.

He started going to volleyball games this year because his daughter is playing. But he talks only with his wife — not others in the crowd.

In the classroom, McDaniel said, he’s cautious about what he chooses to teach and wonders whether he’ll get in trouble.

He still loves teaching and helping children. But “the few that made the accusations hurt you for a long time,” he said.

The 60-year-old plans to retire in five years. “Personally, I can’t wait to leave the town.”

Sometimes, the state’s ethics commission dismisses a complaint if there isn’t enough evidence to discipline a teacher. But it’s rare. Only a few cases — or none at all — are dismissed each year, state records show.

McDaniel found out parents who filed the ethics complaint were upset he used the word “vagina” when explaining the biology behind an orgasm.

They also complained he shared private student information, taught sex education and birth control, and promoted “political candidates” on school property by showing “An Inconvenient Truth,” Al Gore’s documentary on climate change.

McDaniel taught material from a school-approved biology textbook for 17 years, and this was his first complaint.

Teachers get attacked — not necessarily for what they teach, but “because someone doesn’t like them,” he said. “You’ve got to be careful.”

McDaniel doesn’t teach reproductive lessons anymore and wants to stay clear of what got him in trouble. Now, he said, students aren’t getting that instruction.

“The kids are not getting what they need, as far as I’m concerned,” he said, but added there’s a dual-credit medical terminology class offered through the College of Southern Idaho and an animal science class.

The ethics complaint made him more careful of his actions. “It makes you feel like you just have to watch constantly what you’re saying and doing,” McDaniel said.

If an unfair or unfounded allegation is brought against an employee, Idaho Education Association president Penni Cyr said, she hopes the teacher, school district and community will work hard to put that behind them.

But it’s a challenge. “It’s very difficult and very damning on an individual,” said Mike Poe, director of the educational leadership program at Northwest Nazarene University.

School districts and the state typically can’t say much about a case because it’s a personnel matter.

“Oftentimes, a teacher leaves anyway even after they’ve been exonerated because their reputation has been killed,” Poe said.

One protection for teachers: In order to file an ethics complaint, an individual needs to have some stake in the issue.

McDaniel had let his membership to the Idaho Education Association lapse the year the ethics complaint was filed. Now, he’s an active member again.

The association, he said, will stand up for what’s right if you’ve “dotted your i’s and crossed your t’s.” He recommends that every teacher join.

The Association of American Educators encounters unfounded complaints against teachers every day, said Alexandra Freeze, senior director of communications and advocacy.

Even if accusations are false, she said, they could cost teachers thousands of dollars in attorney fees if they don’t have liability insurance, which the Association of American Educators offers. Plus, “they can ruin your reputation.”

When teachers walk into a classroom, they’re looking after other people’s children, which “opens them up to significant liabilities,” Freeze said.

Well-meaning teachers can find themselves in unfortunate situations and need an advocate to guide them, she said. But “we are not interested in protecting teachers who shouldn’t be in the classroom.”

Оставить комментарий

Для комментирования необходимо войти через

![]() Вконтакте

Вконтакте