From WWII to Syria, How Seed Vaults Weather Wars

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault entrance, lit up by fiberoptics the night after its opening.

Svalbard, the Norwegian island halfway between Europe and the North Pole, is a place of extremes. It's the northernmost place in the world where people live year-round. There are no roads between settlements, so everyone gets from town to town by air, sea, or snowmobile. It's home to 2600 people, seven national parks, 23 nature reserves, and several coal mines. But its greatest resource is meant to stay buried in the ground for as long as possible—a collection of 430,000,000 seeds, wrapped in heat-sealed packets, waiting for the end of the world.

The seeds live in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, established in 2008 as the largest seed bank in the world. The Vault protects the world’s agricultural diversity by keeping a stash of seeds secure in a location far from harm. If these seeds' corresponding crops out in the wider world get wiped out by some man-made or natural disaster, the seeds will be brought out to save the day. Until then, these tiny residents, “the final back up," in their caretakers' words, will stay in the Vault, supercooled and super-safe, for hundreds or even thousands of years.

Workers chill out inside Svalbard's Vault 2.

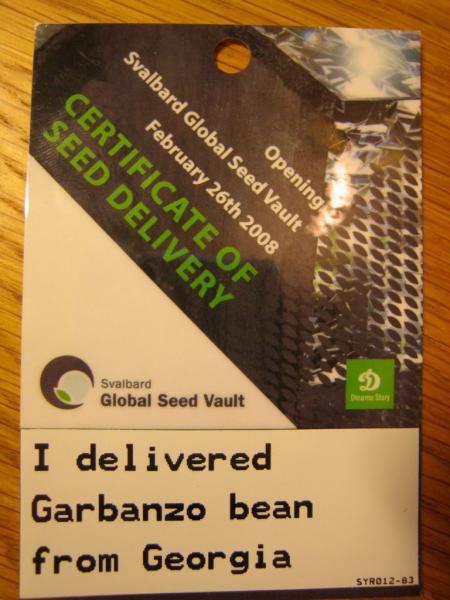

From its completion in 2008 until last month, Svalbard Global Seed Vault's door opened exclusively to welcome new additions—many accompanied by pomp and circumstance, as with this year's visit by potato-toting Andeans, or 2010's pilgrimage by seven U.S. senators bearing chile peppers. This September, the Vault made headlines when it authorized the first ever withdrawal, by the International Center for Agricultural Research in Dry Areas (ICARDA), a global partnership that studies desert- and drought-compatible plants. One of ICARDA's chief seed banks is, or was, in Aleppo, Syria, and it had become more and more difficult for scientists to dodge fighting and manage rebel leaders in order to get to their stocks. They decided to rebuild their collection in nearby Lebanon, which required reclaiming the duplicate seeds they had banked in Svalbard when it opened. "We knew... that Syria was in for an interesting couple of years," Svalbard spokesperson Brian Lainoff told NPR. "This is why we urged them to deposit so early on." ICARDA members will duplicate the seeds again in Lebanon, and send new copies back to Svalbard.

Lainoff said that the Svalbard Vault "did not expect a retrieval this early." It was designed to hold fast, like an ark, for millennia. But though the need for seed banks is often associated with more stereotypically environmental, even futuristic, cataclysms (climate change; disease; pesticide-resistant insects) their history is inextricably tied up with something more banal and present-day—war.

Russia's Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR), lit up at night.

The first global plant bank was created by Nikolai Vavilov, a mind-bogglingly accomplished Soviet botanist who spent his life traveling the world, gathering wild and domestic plants, and attempting to breed them into crops that could sustain his countrymen. He housed his seeds and live specimens at Pavlovsk Experimental Station, near what is now St. Petersburg, where he painstakingly crossed and re-crossed his stock in an attempt to create the ultimate high-yield, disease-free, cold-resistant potato. But you can't breed a war-resistant tuber. In 1941, as World War II raged and German troops advanced on Pavlovsk, the Soviet government frantically removed art from the State Hermitage Museum, but left the 400,000 seeds, roots and fruits on their own. Scientists at the Experimental Station boxed up a cross-section of the live samples, and moved them and the cold-storage seeds to the Station's basement.

They hadn't bargained on the 900-day Siege of Leningrad. As hundreds of thousands of people starved around them, the scientists protected their small cachet of food for the future. They mounted 24-hour watches outside each of 16 seed rooms, kept the potatoes from freezing by burning chunks of bombed buildings, and stabbed increasingly bold rats with metal rods. As the hunger got worse and the taters more tempting, they strengthened their resolve—no one could be alone in a room with the seeds. When some seeds began to molder from lack of dirt, they snuck out to a field to plant them under heavy shelling. They even smuggled a large portion of the collection to a stronghold in the Ural Mountains.

Maize diversity on display in Vavilov's office, itself preserved by VIR.

The siege eventually ended, and much of the remaining collections survived, protected from bombing by their proximity to the Astoria Hotel, where Hitler had been hoping to celebrate victory. But some of the stalwart scientists were less lucky. Peanut specialist Alexander Stchukin died while working at his writing table, and the head of the rice collection, Dmitri Ivanov, starved to death while safekeeping several thousand packs of rice. Those who are still alive remember a feeling of responsibility that outweighed more seemingly immediate concerns. "One of them said ... saving those seeds for future generations and helping the world recover after war was more important than a single person’s comfort,” quotes Gary Paul Nabhan, author of a book about Vavilov.

(Vavilov himself died in a Bolshevik prison. Stalin was a sort of Communist Lamarckian—he believed that acquired traits, like forced early blooming, or Stalinism, were propagated through generations—and when Vavilov refused to condemn Mendelian genetics, he was arrested. He lived for nearly two years off moldy flour and frozen cabbage before finally succumbing, and never recanted his convictions.)

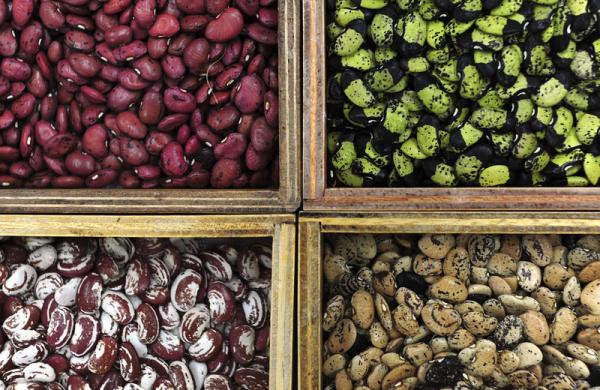

Samples from the CIAT Gene Bank in Colombia.

Since then, virtually no conflict has gone by without a devastating loss of seeds, often mitigated by a heroic rescue or underscored by a tragic attempt. Afghani mujahideen destroyed Kabul's national seed collection in 1992. (Local scientists managed to smuggle some seeds into the basement of a few city houses, but by the time they returned to check on them a decade later, looters had dumped them on the floor in order to steal the storage jars.) During the Georgian civil unrest of 1993, just before the country's Sukhumi Seed Station was destroyed, an 83-year-old botanist named Alexey Fogel escaped into the Caucasus Mountains with its entire lemon collection. Scientist Alexis Rumaziminsi, now known as the "bean boffin of Rwanda," protected the many varieties of beans in his research plots during 1994's civil war and genocide. The US-led invasion of Iraq resulted in the razing of the country's national seed bank in Abu Ghraib—not to mention the implementation of American-style seed laws, which mean that if Iraqis want to buy new seeds, they will have to pay for yearly usage licenses.

The few seeds that Iraqi scientists managed to save were sent in a cardboard box to Aleppo—meaning that those seeds, or their duplicates, have now traveled from their field sites, to Iraq, to Syria, to Svalbard, and, soon, to Lebanon. Despite the alarm caused by the September withdrawal, and the very little it does to alleviate immediate human suffering, this does mean that the Svalbard system is working.

A seed "delivery receipt" from the Svalbard Seed Bank opening ceremonies.

Anthanaios Tsivelikas, the manager of the Morocco ICARDA bank, was sent by headed to Svalbard to gather the seeds. “I was feeling nervous … during the entire journey back,” he told The Independent on October 10. "When you trace back the history of these seeds, you think of the tradition and heritage that they captured." That heritage lies in their cultivation—and now, also, in their preservation, a multinational, multigenerational, often heroic effort to protect the future from the ravages of the present. The seeds may save us someday, but we have to save them first.

Оставить комментарий

Для комментирования необходимо войти через ![]() Вконтакте

Вконтакте