Текст на английском: Derinkuyu & The Underground Cities of Cappadocia

В статье вы прочитаете английский текст по теме городов Каппадокии.

In 1963, a man in the Nevşehir Province of Turkey knocked down a wall of his home. Behind it, he discovered a mysterious room. The man continued digging and soon discovered an intricate tunnel system with additional cave-like rooms. What he had discovered was the ancient Derinkuyu underground city, part of the Cappadocia region in central Anatolia, Turkey.

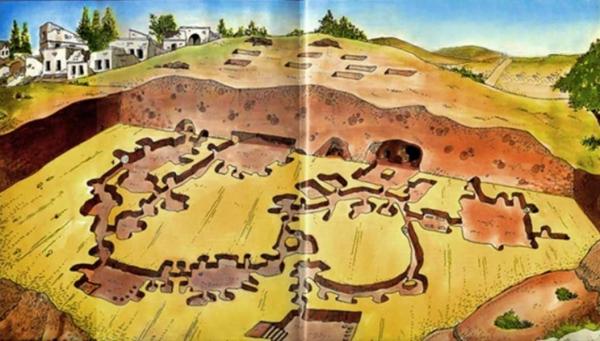

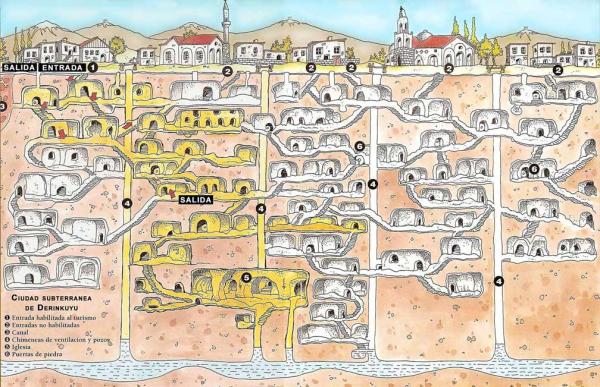

The elaborate subterranean network included discrete entrances, ventilation shafts, wells, and connecting passageways. It was one of dozens of underground cities carved from the rock in Cappadocia thousands of years ago. Hidden for centuries, Derinkuyu‘s underground city is the deepest.

History

The Cappadocia region of Anatolia is rich in volcanic history and sits on a plateau around 3,300 feet (1,000m) tall.

The area was buried in ash millions of years ago, creating the lava domes and rough pyramids seen today. Erosion of the sedimentary rock left pocked spires and stone minarets.

Volcanic ash deposits consist of a softer rock – something the Hittites of Cappadocia discovered thousands of years ago when they began carving out rooms from the rock. It began with storage and underground food lockers; the subterranean voids maintained a constant temperature, protecting the contents from exposure to harsher surface weather extremes.

The underground tunneling would also serve a bigger purpose: Protect the Hittites from attack. The exact dates are unknown, but estimates range the tunnels first appeared between the 15th century and 12th century BCE. The Hittites were believed to have used the tunnels to hide from Phrygian raids.

Those who subscribe to this theory point to the historic account of the Phrygian destruction of Hittite city Hattusa, along with the identification of a small number of Hittite-related artifacts found in the tunnels.

An alternative suggestion has the Phrygians first building the tunnels later, between the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. They explain the discovered Hittite artifacts as being remnants from the spoils of war.

This theory is reinforced by reputation: Phrygian architects are considered by archaeologists to be among the finest of the Iron Age, and known to have engaged in complex construction projects.

Because the Phrygians are known to have possessed the necessary skills and inhabited the region for a long time, they are often credited with first creating the underground city at Derinkuyu.

Less popular is the theory the underground city was the work of the Persians.

Although no direct reference is made to Derinkuyu, the second chapter of the Vendidad (part of the Zoroastrian Avesta) includes a story of “the great and mythical Persian king Yima” who “created palaces underground to house flocks, herds, and men.”

But with no other evidence, this theory has struggled to gain traction among the cognoscenti.

The oldest written reference to the underground cities of Cappadocia was by Xenophon in Anabasis. He mentions the Anatolian people living underground in excavated homes large enough for entire families, their food, and animals.

Because the city was carved from naturally-formed rock, traditional archaeological methods of dating the underground city would fail to discern the origins.

Derinkuyu

Archaeologists believe the underground cities of Cappadocia could number in the hundreds. To date, just six have been excavated.

The underground city at Derinkuyu is neither the largest nor oldest, but it fascinates as it is the deepest of the underground cities and was only recently discovered in 1963. (The largest, Kaymakli, has been inhabited continuously since first constructed).

While there is no consensus for who is responsible for building Derinkuyu, many groups have occupied the underground city over the centuries. It is believed Derinkuyu was later expanded during the Byzantine era (330-1461 CE).

During this time the underground city was known as Malakopea (Greek: Μαλακοπέα). Early Christians used the tunnels to escape persecution during raids from the Muslim Umayyad and Abbasid dynasties.

Over time the need for underground shelter in Cappadocia ebbed and flowed with different ruling empires. In peacetime, tunneling efforts were reduced as resources were diverted back toward the surface. During these times the subterranean city served as cold storage facilities and underground barns.

During the Roman persecutions of the 2nd and 3rd centuries (and the Arab raids between the 8th and 10th centuries) CE, use of the underground cities increased and tunnels were expanded.

Underground City Features

Derinkuyu is the deepest of the discovered underground cities with eight floors – reaching depths of 280 feet (85m) – currently open to the public. Excavation is incomplete, but archaeologists estimate Derinkuyu could contain up to 18 subterranean levels.

Miles of tunnels are blackened from centuries of burning torches. They were strategically carved narrow to force would-be invaders to crawl single-file. Eventually the tunnels reach hundreds of caves large enough to shelter tens of thousands of people.

The build-out of Derinkuyu accommodated for churches, food stores, livestock stalls, wine cellars, and schools. Temporary graveyards were constructed to hold the dead; an ironic twist, bodies were stored underground until it was safe to return them to the surface. Over one hundred unique entrances to Derinkuyu are hidden behind bushes, walls, and courtyards of surface dwellings. Access points were blocked by large circular stone doors, up to 5 feet (1.5m) in diameter and weighing up to 1,100 lbs (500 kilos).

The stone doors (pictured below) protected the underground city from surface threats, and were installed, so each level could be sealed individually. The tunneling architects included thousands of ventilation shafts varying in size up to 100 feet deep (30m).

An underground river filled wells while a rudimentary irrigation system transported drinking water.

Derinkuyu was more than just residences, storage, and tunnels. When residents fled underground, business continued as usual. Commercial spaces included communal meeting areas, dining rooms, grocers, religious places for worship – even shopping. Arsenals stored weapon caches, while hidden escape routes offered residents a last-chance for a getaway.

Unique to Derinkuyu

On the second floor, a barrel-vaulted ceiling tops a spacious room believed to have been a religious school. Rooms to the left provided individual studies.

A staircase between the third and fourth levels takes visitors to a cruciform church measuring approximately 65 x 30 ft (20m x 9m) in size.

A large 180-ft (55m) shaft (pictured above) was likely used as the primary well – both for residents underground and on the surface. To prevent any surface aggressor attempt to poison drinking water, control of the water supply originated from the lower floors and moved upward, with lower floors able to cut off supply to upper levels.

On the third level a 3 mile-long (5 km) tunnel connected Derinkuyu to nearby underground city Kaymakli – although it is no longer functioning as parts of this tunnel have collapsed.

Читайте тексты на английском в этой рубрике.

Оставить комментарий

Для комментирования необходимо войти через ![]() Вконтакте

Вконтакте