How is The Simpsons still on the air?

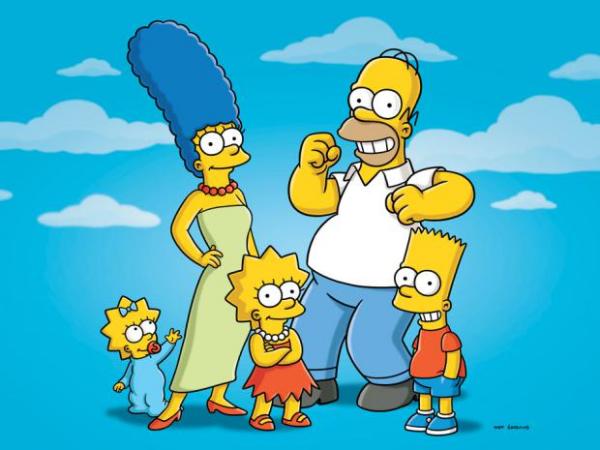

Over the last several weeks The Simpsons has rushed into the public consciousness with an urgency it hasn’t enjoyed in a decade. At Comic-Con last week, in particular, attention was drummed up by the producers grandly, as with galvanic effort they annexed valuable headline real estate across the world. No sooner did Harry Shearer swear to abandon the series than the voice actor announced his triumphant return. One minute Homer and Marge were set to divorce; the next, Matt Groening was loudly assuaging concerns.

Sideshow Bob is set to murder Bart at last, in the reversible fantasy of a Halloween special; Spider-Pig, notable supporting character of The Simpsons Movie, is set to make his television debut. The news even sprawled beyond the frame: the fictitious Duff Beer, fans rejoiced to learn, will soon be available to imbibe in Chile and elsewhere overseas.

The Simpsons enters its 27th season this September. That staggering number accounts, I think, for the tang of desperation clinging to the rumours and news: it’s surely difficult, after 27 years of The Simpsons, to remind people that it still exists and persuade them that it’s still interesting. Of course the truth is that it no longer is interesting — and it no longer should exist. Why do we accept the pretence that the show remains somehow relevant? It hasn’t been this century. What we ought to hope for now isn’t an intriguing 27th season but a cancellation order.

In 1997, eight years into its sprawling run, The Simpsons aired “The Itchy & Scratchy & Poochie Show,” in which, with self-referential irony, the writers addressed the challenge of the show’s waning appeal. “There’s not really anything wrong with the Itchy and Scratchy show,” Lisa at one point observes. “It’s as good as ever. But after so many years the characters just can’t have the same impact they once had.” This proves a wise diagnosis — and a fate the writers of The Simpsons seem resigned to. But nearly 20 years later this kind of familiarity is no longer the problem. The problem is simply that The Simpsons hasn’t been good in a long time.

The golden age of The Simpsons is widely agreed to span its third to eighth season, give or a take a year depending on the age and affections of the respondent. And yet “golden age” is misleading. Across these years The Simpsons was indeed an extraordinary, even masterful thing, an animated sitcom of such inspired genius that no degree of praise could seem an overstatement. But “golden age” brings to mind the crest of a rolling hill, on either side of which greatness slopes steadily down to mediocrity; in the case of The Simpsons its exemplary years are bordered to the right by a sudden, startling drop, beginning (for me) with the plummet of Season 9. By seasons 10 and 11, the show is in gaping valley, staring way, way up at the apex left behind not long ago. It would never get anywhere near those heights again.

It’s hard to account for the decline. For me an eighth-season episode, “Homer’s Enemy,” seems in retrospect a harbinger of the miseries to come: Homer’s rivalry with poor Frank Grimes, though occasionally uproarious, offered a glimpse of the mean-spiritedness and meta-humour that would soon come to define the sensibility of the show’s middle period, when a cruel streak and in-jokes about internal logic began to take the place of the sweetness and warmth that had been the heart of The Simpsons from the beginning. Those with a higher tolerance than me for bitterness might lay the blame for the slump elsewhere. Either way, the real trouble was the same: the show stopped being so funny.

The late ’90s and early 2000s yielded a few sturdy episodes and a clutch of memorable gags, to be sure. (I’m fond of an 11th-season one-liner that credits a sitcom’s six-episode run as “the longest-running series in British TV history,” to take one example.) But even at this stage the show had been reduced from a comedy in which every moment was funny to one that could only intermittently make a punchline stick. Then came the seismic change: the switch, in 2009, to high-definition, which took the already overhauled digital animation integrated several years before and contemporized it to suit a more modern aesthetic. From this point on The Simpsons didn’t even look like The Simpsons. Now it looks garish and conspicuously slick, streamlined and computer-perfected but devoid of its former hand-drawn flair.

Today I find The Simpsons virtually unwatchable. It feels baggy and lumpen, stilted with dead air; the characters and locations are recognizable, but put to use in a way that strikes me as closer to fan-fiction than a continuation of a once-beloved thing. The Simpsons enjoyed five perfect years and perhaps three or four very good ones. But think of how dwarfed that greatness is by the deluge of later dreck: 18 terrible seasons tower well above the worthwhile ones. More Simpsons is not the answer, whatever marginal uptick they might muster. So let’s resolve to stop pretending to care. Forget promises of divorce or Sideshow Bob’s revenge. Let The Simpsons itself be put to rest. Let it die. The only good it has left to give is to end.

Оставить комментарий

Для комментирования необходимо войти через ![]() Вконтакте

Вконтакте